Following a wave of multi-year club options attached to deals, players and their agents have begun to request and receive player options in recent years as well. David Price, Johnny Cueto, and Jason Heyward have each received them this winter, meaning that quantification of such deals is essential for careful team building. (Editor’s note: this article was written before the Dodgers reached an agreement with Scott Kazmir.) Everyone up to the commissioner has expressed concern that these “opt-out” clauses have been included in deals, and some feel teams simply should not give them. However, this is akin to saying that teams should not pay players above the league minimum salary—of course teams would like to do this, but you need to give players compensation to sign them. An opt-out is a way to lower the cost in dollars to the team, because the player will want more money otherwise.

Each of these three deals would be substantially more expensive without opt-out provisions—each opt-out clause is worth around $20MM, by my calculations. To test this, I looked at how a rough weighting of previous years’ WAR would affect a future projection, and compared this to how that projection would crystalize as it got closer. This led to an estimate that a very rough projection of future value 2-3 years in advance would change by about 1.0 WAR over the following 2-3 years. A more sophisticated system would probably change by about 0.7 WAR as it gets closer—and dollar value would probably change by about $7MM per year after accounting for overall uncertainty in salary levels. (The relationship between dollars and WAR utilized in this post is explained at this link.)

Given that potential level of variation, there are still a wide band of possibilities in terms of what a given player’s expected future value will be at the point of decision on an opt-out. But at base, an opt out is a binary choice: yes or no. Based on what we know now, and based on reasonable projections, we can estimate a given player’s future expected value at that point of decision by weighting different possible outcomes.

In other words, if Player X opts out, we can assume it is because his anticipated value at the point of that decision is higher than that which he would have earned through the remaining portion of the contract. But we don’t know exactly how much higher. So, to arrive at a value for the scenario in which a player does opt out, I’ve weighted all of those possibilities and reduced them to a single dollar value. The same holds true of the situations in which the player does not opt out.

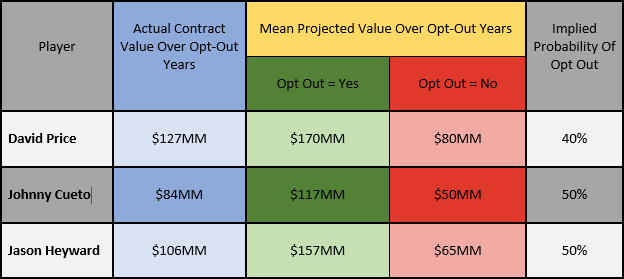

We’ll get into each player’s situation further below, but this table shows the results of the exercise. (App users can click on this link to see the table image.)

David Price received a contract for seven years at $217MM, but it was really a three-year contract for $90MM with a player option of four years and $127MM. If Price only held teams to a three-year commitment, he would probably get close to $120MM—but this is not what he did. Instead, he will require $127MM for 2019-22, only on the condition that he looks to be worth less than that by then. Although $127MM is not a terrible estimate of his 2019-22 production as of January 2016, this value will probably change drastically by October 2018, one way or the other. If he does not opt out, he probably will have performed worse, and conditional on the assumption that he will not have opted out, I estimate his expected value for his 2019-22 seasons to be $80MM. If he does opt out, he probably will have performed better, and conditional on the assumption that he will have opted out, I estimate his expected value for those seasons to be $170MM. Given that this corresponds to roughly a 40% chance of opting out, his opt-out clause is worth about $17MM, meaning that his seven-year $217MM contract is roughly equivalent to a seven-year $234MM contract with no opt-out clause.

Johnny Cueto’s contract is somewhat trickier, but it essentially amounts to a deal of two years for $46MM, with a player option of four years and $84MM, followed by a club option of one year for $16MM. Cueto would probably be worth $17MM above his salary for 2016-17. But for 2018-21, he is likely to be worth $50MM if he does not opt out and $117MM if he does. With roughly even odds of opting out, this makes his opt-out worth about $17MM. While the club option for 2022 makes the deal somewhat more attractive for the Giants, the odds that he will be worth much more than this are low. Overall, Cueto’s six-year deal for $130MM would probably cost about $147MM with no opt-out clause.

Jason Heyward’s contract is even trickier, but it mostly boils down to a three-year deal for $78MM, followed by a five-year player option for $106MM—except that the first player option (if exercised) is only certain to include one more year for $20MM. That’s because there’s a vesting provision that, if triggered—by Heyward reaching 550 plate appearances in the season following the initial option decision—would give him yet another player option for four years and $86MM. (If he exercises the initial option but then doesn’t reach that PA threshold, then both sides would be stuck with the remaining four years of the contract.) Heyward’s value is further complicated by the fact that signing him required forfeiting a draft pick, which is worth around $9MM.

Although Heyward’s contract contains two opt-outs, it is not all that likely that he opts out after 2019 if he does not after 2018. Players’ values do change substantially, but he is likely to be either much more valuable than his five-year player option after 2018, or much less valuable. It is not that we expect his value to look similar after 2018 and 2019—it is that he will probably already be way above or way below the current expected value near $20MM per year, and is likely to remain way above or way below this line through 2019.

For the first three years of Heyward’s contract, I estimate that he is worth about $22MM more than his contract will pay him. With five years of player option, there is a wide range of potential values afterward. I estimate that he also has about even odds of opting out, but if he does not opt out then he is probably only worth $65MM, while if he does he would be worth $157MM. If he doesn’t opt out after 2018 and does after 2019, he is likely near the middle and the value of the second opt-out is small. The net effect is that his opt-out clauses are worth about $25MM, and he would probably have received $209MM for eight years instead of $184MM had no opt-out been included in the deal.

With values of $17MM for each of the two pitchers and $25MM for Heyward’s pair of opt-outs, these opt-outs help keep costs down for teams. While they contain more downside and less upside than typical free agent contracts, they cost less money as well. As teams move forward in this new market, they should be careful to properly consider the true cost of these player options. If teams are willing to expose themselves to some downside risk, they can lower the cost of acquiring elite players.

Very nice analysis, well done mlbtr!

Seconded. Excellent content. Thanks!

Nice piece. A quick question. Do you adjust for the possibility of season-ending “catastrophic” injuries and are there different rates for pitchers and position players? Presumably, a pitcher out with TJ or labrum surgery would take 12 months or more to get back on the field, plus additional time ramping up innings. There aren’t that many comparable injuries for position players. How would that factor into the value of the opt out, or is it so uncommon as opposed to the pool of all players, that it wouldn’t really be a factor in your calculation?

Don’t want to speak for Matt, but I’d assume this is essentially accounted for a) in the risk premium that went into the actual contract and b) as one of the possible outcomes blended into the “No” opt-out value.

On a somewhat related point, for an interesting thought experiment, you could kind of blend the John Lackey/Red Sox contract with Cueto’s deal. Say he had received an opt out after two years and the deal still included a team option at the back end. In that case, Boston’s downside was exactly what happened: he had two bad years, didn’t opt out, and then had TJ and missed an entire season. Of course, he was still a talented player, and came back and delivered some value — enough that it made sense to pick up the option. (Obviously, that’s much easier when it’s valued at league minimum, but Cueto’s may well prove to be relatively cheap at $16MM.)

The overall $ and WAR that resulted in Lackey’s case would, presumably, make one possible point on the continuum when looking ahead for Price/Cueto.

Thanks very much for the reply. The Lackey clause is interesting because it effectively created an undervalued asset for the Red Sox to sell–as compensation for paying for an injured year–because Lackey regained some of his former form. The Cueto option, if he’s pitching well, wouldn’t create the same excess dollar-amount value, but still would be useful.

Of course, the risk in the Lackey deal was the total production during the 6 years he was under contract to Boston–702 IP, and a total of 4 bWAR. You also wonder if the warning signs the Red Sox might have seen in Lackey’s last year with the Angels (1.8 bWAR) aren’t also present in Cueto (his time with KC). Kind of leaves you with an interesting question, especially for pitchers. If you were insuring against injury, what years would you spend the most on, if given the option? I

These opt-outs are bad for baseball.

There’s no reason a club should be doing them, they’re only good for the player at all in any form. The team gets zero value out of giving an opt-out, as the only reason a player wouldn’t exercise it, is if they’re performing under the value of their contract.

I know there’s a %50 estimate, but the only scenario where Heyward doesn’t opt out, is one where the contract is bad for the team. That isn’t a very good idea to me.

I agree 100 %.

If the player was dropping his OVERALL contract value by 15%-20% in order to have this feature added, it wouldn’t bother me so much.

Adding an opt out could be the difference between landing a player or not though

Not to mention it gives the player an added incentive to perform at a high level during those pre opt-out years that wouldn’t be there otherwise. Is this not beneficial to the team also?

But if a player only performs well to get paid at his opt-out, do you want that attitude in the clubhouse?

Maybe, maybe not.

Was Zack Greinke perceived to be a clubhouse problem with the Dodgers by putting up an historic season in 2015 before opting-out into free agency?

Winning is the best promoter of a good clubhouse and better individual production generally contributes to a favorable team record.

Greinke is special though. He had three good years, not just one…I feel that the Maeda contract is brilliant, in that it’s a win-win. Only $25mil guaranteed, and he actually has to perform well to be paid well. What a simple concept. It marries the long-term with incentive-laden.

My thought is that Greinke was not a distraction or negative clubhouse guy due to his opt out and neither was Sabathia. Obviously the jury is still out on Greinke, but the Yankees could have saved themselves by not giving in the Sabathia or Arod when they used their opt out. I prefer that the Sox gave Price an opt out because he will continue to be motivated but meanwhile if he is amazing (which I am ok with) then he will opt out after 3/90. They had no chance of signing him for 3/90 in the first place and they would get a draft pick. Then, if he is terrible then you are stuck with him whether he has it or not. But chances are he will not decline horribly in his age 30-32 seasons. So they just have to have the self control to not extend him for his age 33+ seasons (should he opt out). Greinke will be interesting to watch because if he drops off in Arizona then the Dodgers will have saved themselves.

In terms of production, the notion of a player opt-out may become the new norm in MLB since vesting options have restrictions that are limited to things like games played, plate appearances, innings pitched and performance awards and cannot be tied directly to specific production numbers like BA, HR’s, RBI’s, ERA or even advanced sabermetrics.

From a certain perspective, the opt-out may be a way to circumvent the current rules regarding the restriction placed on vesting options which are deemed necessary to maintain the integrity of the game and not promote individual statistics above the concept of team play.

The value the team gets is the player, at a lesser price than they would have received without the opt-out clause.

By this logic, why would a team ever pay a player at all? It’s bad for the team.

Are you really going with that?

As a Giants fan I am really hoping Cueto pitches awesome for the first two year and opts out.

I agree – it is a win all the way around if he does

“There’s no reason a club should be doing them, they’re only good for the player at all in any form.”

Not exactly true.

“While they contain more downside and less upside than typical free agent contracts, they cost less money as well.”

Opt-outs clearly benefit the player, but teams aren’t stupid. The whole point of this article is that there is a dollar value that can be placed on opt-outs. I’m sure the teams including these clauses have factored in that value. In fact, after reading this, and noticing that the total contract when factoring in the opt-out value is roughly what these players were projected to earn, I’m even more positive that teams are applying the proper monetary value to such clauses.

“These opt-outs are bad for baseball.”

I just don’t see this at all. The argument can be made that they are bad for teams, given that they assume all the risk for a more limited reward (but as this article shows, that risk is somewhat mitigated by a cheaper AAV), but how is this bad for baseball? Small market teams aren’t usually in on big free agents regardless of opt-outs, because they can’t afford to take the risk in the first place. All the opt-outs do is give the elite players worthy of demanding them a chance at earning more money. With revenue exploding across the game, I’m glad to see players getting creative in order to get the biggest piece of pie they can.

Thats the thing though, contract negotiations is all about compromising. Player A wants lets say $25 AAV (since that’s the number that counts against the cap). Team A wants to sign Player A, but not at $25. As a compromise, Team A offers an opt-out after two to four years (depending on contract length) that will allow the player to get back on the market if he plays well with the exchange being the AAV is lower than what the player would want and at a number that is more appealing to the team.

The other choice is to either wait for the player’s price to go down (which is risky as he could sign elsewhere) or offer him a contract based on what he wants in terms of AAV and length (which in a few years might result in overpaying a player for poor production. For a guy like Heyward who is 26, his age gives him time to get at least one more big contract. The guy isn’t going to sign a long term contract worth $18-$20 AAV if he wants to maximize earning potential. The smartest move for him would be to sign a contract for what team’s feel is his fair value and ask for an opt-out after a few years. It allows him to get back on the market one more time, assuming he played well.

From a marketing/branding standpoint, how does a team convince their fan base that they now have a “franchise” player to build around, given the pervasiveness of these opt-outs? For example, does a 2018 Cubs fan buy a Heyward Jersey? He’ll likely be out of town the following year.

The league is flush with cash, and opt-outs are only going to help the player more and hurt the ownership with compromised contracts (I know, poor owners, right?) But the FANS matter too. My main concern is that opt-out will become the new normal, while no-trade clauses are sufficient to protect a player. Incentive based contracts protect the team.

Then again, the owners are signing these agreements on the dotted line, so hopefully realize the downside.

Why would any Cubs fan wait until 2018 to buy a Heyward jersey? Buy one now!!

“Heyward is the franchise guy?!” – Kris Bryant

Funny the commissioner has a problem with player options but not club options. I refuse to buy any notion that player options are unfair to teams when both sides are free to negotiate money and terms.

I think you are confusing the way “player option” is used in this article to describe opt-outs. The only club option I have heard of is the club has the option to add another year to a players contract at x amount of dollars. If teams were getting “club options” equal to the way “player option” is being used when signing contracts it would be akin to voiding a contract after x amount of years if the player performs badly. I have never heard of a contract where a team has the option to void the last few years and if one was ever agreed to the union would riot for sure.

I’m fine if Cueto opts out. That would mean he dealt for 2 years and Giants wouldn’t have to pay for him in his declining years!

This assumes they don’t try to resign him.

Very interesting analysis. Much more interesting than the usual speculation! One question: how do you calculate the implied probabilities?

What would make sense to me would be to find the probability for which the weighted average of your estimated values equals the true value of those opt out years, but that gives me 48% for Price, which I can’t tally with your numbers even with generous rounding.

Also, would it be right to think that a lower implied probability suggests a better deal for the team? I guess it depends on your view of the value of the actual contract signed.

I’m curious about the implied opt out % as well. Seem arbitrary but maybe I missed something.

Based on the methodology it seems like a higher opt out chance implies more “savings” for the contract. In the David Price example:

(Opt Out Value – Contract Value) x Implied% = Value of Clause

OR

(170 – 127) x 40% = 17

If that percentage was lower (less likely to opt out) then the expected savings wouldn’t amount to as much. However, if you could already assume a lower probability of opt out it’s hard to imagine the player wanting it in his contract in the first place.

It’s a double edged sword, perform well, the club progresses, and opt out, yes you could go somewhere else for more money. Lets hypothesis that Giants win 2016 WS, and Cueto has a Sub2 ERA in 2017 and Giants are ok but don’t win anything. Would Cueto go to another club for more money, if the Giants stock pile for a run in 2018?!

If it were me, after that, I would want a third WS ring if I was Cueto. But I am not Cueto. Depends what he prefers more ridiculous amounts of money further on in his declining years or more rings. I personally would go with rings. But let’s see what Giants do in 2016 first before we start thinking about Cuetos other 6 potential years, in this contract.

If he already has two rings I could see him cashing out somewhere for a long term deal and assuming he can get a ring somewhere else anyways. The fans will always see it as ring vs. money but the player often assumes they can have both. Then, of course, some players just don’t care about winning and just get the paycheck, but I like to think that isn’t always the case. In baseball I think it is rare for the team handing out the biggest deal to not have a chance to compete. Maybe the DBacks make a push this year.

Yes that’s also true, but how much more money does anyone need in Baseball and Soccer/Football this is getting ridiculous isn’t it. Good that there is a calm on the free agent front, hopefully this will bring the prices down to parity.

It is was me, and I just won a ring in 2016, and in all likelihood the team is going for another run in 2018, I would rather stick to what I know and go with the present team rather than change clubs for $5 mil a year more with new surroundings new role and with a less likelihood of winning, because let’s Face it Giants are quite good in the postseason will the new team have the experience of the same. What if he goes to the Pirates, I don’t expect them to win even with Cutch, they are a wild card team. The same with Cubbies, I don’t expect them to win in 2016, 2018-19 maybe with experience of the playoffs, but with that division and lack of experience, not in 2016.

I love your analysis, as usual, Matt.

I’m having problems coming up with the numbers you are getting for the value of the opt-outs of $17M, $17M, and $25M. Is there any chance you can go through the details of how you calculated each?

Here is what I see from the table above that you provided. Oh, OK, I see my error now, but since I typed most of this up already, I’ll just post for those also curious. My error was using the red column value for the non-opt-out when I should have been using the blue, since that is what he would get if he didn’t opt-out.

For Price, the rest of his contract is worth $127M. If he opts out, average value of $170M. There is 40% chance of that. If he don’t, average value of $80M, with 60% chance. From what elemental stats I remember, I multiply $170M by 40% and add to $127M times 60% to get the expected value of $144.2M, or $17.2M.

For Cueto, it’s $84M, with opt-out of $117M/50% and no opt-out of $50M/50%. That works out to $100.5M or $16.5M.

I’m still not sure how you came up with the implied probability of opt-out. How did Cueto end up at 50%? Given his historic production, I’ve been guessing that the odds of him opting out is pretty likely, as he would need to sink below average WAR production to not want to opt-out and get a new contract in two years. That to me implies a catastrophic decline would need to happen, but he’s mostly been healthy and very productive,

I don’t understand where you got the numbers for the “projected value over opt out years”.Using Price’s contract as an example, he gets $127MM the last 4 years.These are the terms both sides agreed upon.

If he does poorly you figure his deal is only worth $80MM those last 4 years and Boston will eat $47MM of “unearned” payroll. Is the $80MM your assumption or is there some algebra that shows how you came up with the number. I am not saying it is wrong, just don’t know how you got there.

Now if he does well and opts out,you estimate his expected value to be $170MM for years 2019-2022. So to figure out if Price really would want to jump out into FA, he would look for a team to pay him an AAV of $42.5MM for his age 33-36 seasons. My guess is the % is closer to -0- than to 40%. I also question the statement that his contract would be worth $234MM with no opt out. Those kind of numbers were never talked about and he actually got the “$30MM+ AAV” they wanted. That would be true only if a team was willing to actually pay him that much.

Not sure how your math takes into account real life actions and the “industry reasoning” that the last +/- 2 years of a contract is lost money.

Someone please help me understand what I am missing since most posters seem to understand these numbers.