Having already recently examined overall trends in the inclusion of options in contracts, we’ll now take a look at the different types of options. The four most common types of options are: (a) club options, (b) vesting/club options, (c) mutual options, and (d) player options or opt-outs. There are many variations of these approaches that crop up in individual contracts, including player options or voiding rights that vest upon conditions (including trades) as well as variable guarantees.

For looking at aggregated numbers, it makes sense to focus on those contract terms most commonly utilized. (All data refers to the six signing seasons between 2007-08 and 2012-13.) Player options and opt-outs are fairly scarce, highly individualized, and often intermingled with other complicated contract provisions. Accordingly, we’ll leave those for another day. (In the meantime, see here for some recent examples of opt-out clauses.)

Club Options

By far the most common brand of option is the simple club option. The proposition is straightforward: after the last guaranteed year of a contract, the club can elect to keep control over the player for one (or more) seasons. If not, usually the team must pay a lesser buyout sum if it declines the option.

Risks And Benefits

There are several salient features of club options that make them highly beneficial to teams. First, they allow the team to defer the buyout portion of the guaranteed total salary to a later season. Second, they afford the team one or more seasons of control without guaranteeing the player’s salary. And third, unlike retaining rights to tender a contract through arbitration, club option years come with a specified price tag.

On the other side of the ledger, club options can benefit players somewhat, particularly if the buyout makes up a sizeable portion of option price. After all, the effective decision for a team with a club option is whether or not to pay the difference between the option price and the guaranteed buyout. (For example, an $11MM option with a $4MM buyout becomes a $7MM decision for the club.) Hence, if a player’s value falls somewhere between the full value of the option and the value of the option less the buyout, the team may ultimately overpay (on an annual basis, at least) to retain the player.

Likewise, the fact that the team will — at the point an option comes due for decision — have the chance to retain the player on a one-year commitment (or, in the case of multi-year options, retain rights over future seasons) can create incentives in favor of overpaying for a single season. On the other hand, of course, those factors also tend to prevent the player from achieving a new, multi-year deal on the open market.

Recent Usage

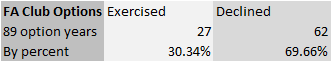

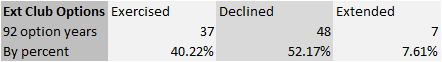

We already know from the first part of this series that extensions are more likely to contain option clauses than are free agent deals. It is further apparent, moreover, that the club options obtained through extension tend to come at more favorable prices. Among club options that have matured (i.e., have come up for a yay or nay), and were not otherwise disposed of (such as through a voiding clause or retirement), it appears that free agent club options were significantly less likely to be favorably acted upon than extension club options:

In the case of extensions, a second extension served in several cases to act, in effect, as a favorable exercise of what originated as an option year. (In some cases, the option is formally exercised in the course of reaching an extension; though it can be unclear, I have attempted to categorize such situations as an affirmative exercise rather than putting them in the “extended” category.) Adding those situations to those where the option was exercised outright, we see that it is about 50% more likely (~48% vs. ~30%) that a club option will be exercised if it comes from an extension rather than a contract signed with an open-market player.

This phenomenon is likely a reflection both of the differences in bargaining power and the fact that extended players are often (but certainly not always) at a younger point on the aging curve. Combined, it seems apparent that the option years of extended players are more likely to be good values at the time they come due for decision.

In turn, these observations inform how we assess the value of club options for new contracts. Club options are exercised somewhat less than one third of the time in the case of a free agent. And they are roughly 50-50 propositions when agreed upon via extension.

Click below to read about vesting/club options and mutual options.

Vesting/Club Options

A common variation on the club option contains vesting provisions that allow the option year to become guaranteed upon the fulfillment of certain milestones. Given the MLB’s constraints on permissible metrics for conditioning contracts, vesting provisions (like incentive clauses) generally rely upon accumulation of innings, games finished, or plate appearances rather than tying directly to performance.

Risks And Benefits

Adding a vesting provision to a club option obviously tilts things back in the direction of the player. Though teams still have control over playing time, and thus have the ability to prevent an option from vesting, the team also has countervailing incentives to allow the player to achieve the vesting clause.

Among them, of course, is that the team wants to benefit from the player’s performance — so long as it is beneficial. And teams must be careful to avoid overt measures designed to avoid triggering a vesting clause, as they could hypothetically run the risk of a grievance action.

From a player’s perspective, a vesting clause may provide some protection against being overused and then left to navigate a skeptical open market. It also can pass some upside to the player that rewards for past performance, rather than paying for anticipated future performance. In short, a vesting clause can open up an avenue to a sizeable, one-year payday that might not have been available through free agency. (For instance, Bobby Abreu played every day in 2011 at replacement level, leaving the Angels on the hook for $9MM when his option vested. He had 27 plate appearances for the Halos in 2012.)

Age is a notable factor of vesting/club options. Though several players have agreed to extensions that include vesting/club options, only two – Madison Bumgarner and Elvis Andrus – have done so with less than five years of service time.

Recent Usage

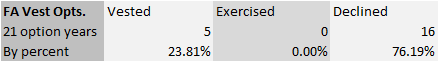

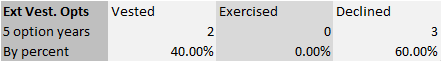

Clearly, the dataset is fairly sparse, especially with respect to extension situations. (Remember, of course, that there are additional vesting/club option scenarios from the 2007-08 through 2012-13 period that have yet to reach fruition.)

All said, vesting/club options look roughly as likely to be triggered as are club options, albeit by vesting rather than club choice. Perhaps unsurprisingly, when players fail to play enough (and/or well enough) to cause the option to vest, teams have been uninterested in nevertheless taking on the obligation. This confirms the findings of MLBTR's Zach Links, who broke down recent vesting provisions using a slightly different dataset.

Of course, every vesting situation is different, making it difficult to draw conclusions about general expectations for how likely a given clause is to vest. Some — like Justin Verlander’s 2020 option (vests at $22MM with top-5 Cy Young vote from prior season) — are tied expressly to outstanding performance. Then, there are option provisions that are heavily tied to opportunity and are readily susceptible to control by the team, as in the example of games finished, a common vesting provision for relievers. Though not a vesting situation, Jose Veras's 2014 club option increased in value – and, somewhat surprisingly, was ultimately not exercised — when the Tigers let him finish a meaningless game in a non-save situation late in the year.

Still other vesting/club options are tied mostly to the ability to stay on the field. In some cases — such as the 2014 option of Roy Halladay, which did not vest when he failed to throw 415 innings across 2012-13 — the contract sets aggressive bars that require health and excellence to be reached. Alternatively, playing-time goalposts can be designed primarily to protect the team against major injury or performance issues. For instance, the Phillies' Jimmy Rollins has a 2015 option that vests with 1,100 plate appearances over 2013-14, and turns into competing club and player options — you might label it a "cross option" — if it does not vest. Likewise, teammate Chase Utley's deal includes a series of three vesting/club options that spring to life with 500 plate appearances; if those options do not vest, they become club options with values that vary based on how much time Utley spent on the DL in the prior year.

Nevertheless, the numbers confirm what is generally understood: in exchange for allowing players the ability to play their way into additional guaranteed money, teams generally set demanding vesting levels that are infrequently met. It is somewhat curious, however, that the option values are generally not also dropped to a level that would leave them still attractive to teams in the event that the option does not vest. Viewed this way, while vesting/club options theoretically carry countervailing benefits and risks, it appears that they have been implemented mostly as a hard-to-reach, pure player benefit over recent years.

The Rollins and (especially) Utley contracts, however, look to be instances where an alternative purpose was being served by a vesting/club option. In both cases, it is not difficult to imagine a reasonable scenario where the Phillies exercise the option even if it does not vest. This is particularly so with regard to Utley, since the value of the club option floats downward based on time spent on the DL and because the club would lose its future option rights by declining. It will be interesting to see whether those models are emulated in the future, especially for excellent-but-aging veterans in the clone of the Philly middle infield duo.

Mutual Options

Finally, we’ll look at mutual options, which of course require both player and team to agree to accept the salary provided in the option year. Generally, mutual options include a buyout owed by the team if it does not exercise its end of the option. If, instead, the player declines his side, he usually sacrifices some or all of the buyout.

Risks And Benefits

At first glance, the recent innovation of the mutual option seems useful mostly as a mechanism to backload portions of the contract. As Wendy Thurm of Fangraphs has explained, however, mutual options can have other uses. For one, they allow both player and team to hedge somewhat against shifts in that player’s value (due to performance or market changes): if it falls, the team can simply pay the buyout and move on; if it rises, the player can sacrifice the buyout and look for a new deal.

Additionally, Thurm rightly notes, the mutual option can theoretically reduce transaction costs and provide an avenue for player and team to sidestep the risk of market fluctuations. Rather than negotiating anew or subjecting things to the always-shifting free agent market, both sides can simply opt to accept the previously agreed-upon terms, with the buyout amount also possibly also acting to encourage a deal.

Recent Usage

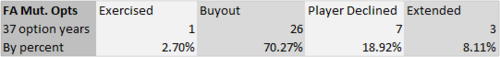

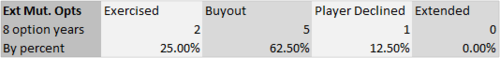

Indeed, while mutual options are rarely exercised, they are not without impact. Of the 45 total mutual options agreed to over the 2007-08 through 2012-13 timeframe that have come up for decision, three were exercised and three others were made obsolete by an extension.

Obviously, buyouts are the most common result in a mutual option scenario — approximately the same likelihood as in the club option scenario, in fact. What is different, then, is the result that occurs when a team feels the option is worth exercising.

The mutual option simply offers a different cost-benefit scenario for teams and players. As the numbers (and common sense) demonstrate, the upside to the mutual option scenario resides largely in the player. The key distinction from the club option lies in that roughly 30% of players who control their own fate after their team elects to exercise its end of the option. The player can either take the money in hand or, as occurs in most cases, seek more money and/or better opportunities on the open market.

Clearly, it is quite rare for the team and player incentives to align in favor of mutual exercise of the option. While it makes intuitive sense that the pre-negotiated terms might have some momentum effect, or at least limit transaction costs, the effects have been somewhat limited. Just three of 45 mutual option years from our dataset (6.67%) were exercised.

That is a non-negligible likelihood, but still fairly rare. All three instances of an exercised mutual option involved modest raises for veterans with somewhat analogous skillsets: Matt Belisle (Rockies, 2014, durable middle reliever), Brian Moehler (Astros, 2010, mediocre innings eater), and Miguel Olivo (Royals, 2009, sturdy backstop). Another exercised mutual option — the $1MM 2012 option between Jason Giambi and the Rockies — also fits that mold, but is not part of the dataset because it came as part of a minor league deal. In each case, perhaps, it was worth it to both team and player to limit their exposure to market risks by simply taking the deal that was already on the table.

And then there are the extension situations. While it would be pure speculation to assert that the presence of an upcoming mutual option decision played a role in the three extensions noted in the table, each of those extensions – Jake Westbrook (2013), Jeff Francoeur (2012), and Brett Myers (2011 option) – were reached during the month of August, just months before the mutual option was to be decided for the ensuing season. It is not outside the realm of possibility that the continuing obligations between player and team helped ease the way or even created some impetus toward a new deal.

Thanks to Tim Dierkes and Steve Adams of MLBTR for suggesting additions and improvements to this piece.

Can you use a buyout on a club option and then re-sign him at a lower price? Or are there rules with regards to that?