The competitive balance tax has been an insidious force against the players. Back in 1996, in the wake of the ’94 strike, a new collective bargaining agreement was reached and healing between the teams and players could begin. As Jon Pessah wrote in his book The Game, “[Union head Donald] Fehr finally said yes to a luxury tax — the first time the union agreed to any form of payroll restraint since free agency changed everything in 1976.” I don’t think anyone anticipated what the luxury tax would become.

In that CBA, which covered 1997-2001, the luxury tax was to cover only the 1997-1999 seasons, sort of an experiment. Opening the door to the luxury tax in that 1996 deal wasn’t perceived as a major hit to the players. Pessah wrote, “This labor war was a huge victory for Fehr and the union…The owners never got their salary cap or any changes to free agency or salary arbitration.”

Fast forward to 2021, and it’s clear that most major market teams use the base tax threshold of $210MM as something of a soft salary cap. It’s a limitation MLB likes having in place, as it helps keep free agent salaries down. If MLB wanted the luxury tax removed, they could do so easily, as they did when it was decided the tax would not be collected in 2020.

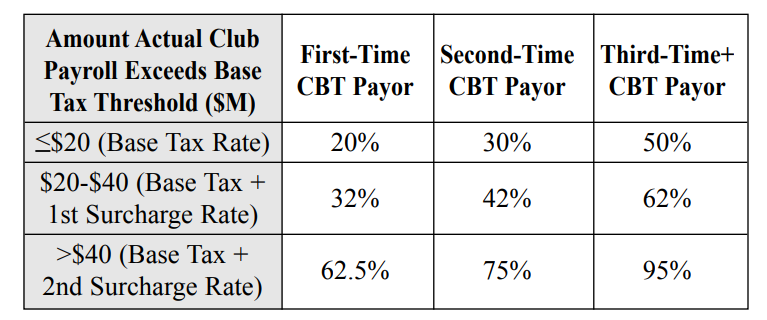

Here’s the chart for tax rates (link for app users):

The tax brackets for 2021 are $210-$230MM, $230-250MM, and $250MM and beyond.

In their extrapolated 2020 payrolls, the Yankees, Astros, and Cubs exceeded that year’s $208MM base tax threshold. It’s notable that while MLB did not make these three teams actually pay tax in 2020, they still didn’t give them a free reset. That’s why the Yankees sit around $200MM right now – they’re in that third column of the chart, and they want to move back into the first for 2022. It’s all about the reset, not the actual tax amount if they slightly exceed $210MM in 2021.

The Cubs are trying to avoid the third-time CBT payor column as well, and they’ve accomplished that goal and then some in getting Yu Darvish, Jon Lester, Tyler Chatwood, Jose Quintana, and Kyle Schwarber off the books. They’re only around $170MM for 2021, a full $40MM shy of the threshold. The Astros are sitting around $196MM, so they have wiggle room as well. The machinations of these three teams, particularly the Yankees, assume that the luxury tax system will remain similar in a new CBA, and there actually is a reason to reset in 2021. If the union succeeds in drastically increasing the thresholds, which should be a major priority for them, all three clubs could have easily reset in 2022 anyway.

The one club that didn’t get the memo about treating $210MM as a soft cap is the Dodgers. The Dodgers pulled off their reset in 2018 and have stayed below the base tax threshold since, putting them in the first-time payor column for 2021 after the signings of Trevor Bauer, Justin Turner, and Blake Treinen. With a projected CBT payroll of $254.4MM currently, they’re looking at a tax penalty of about $13MM for 2021. If a third-time payor spent $254.4MM, their tax penalty would be over $26MM. In any case, exceeding $250MM places another tax: the club’s highest available pick moves back 10 spots in the next draft. That’s why the Dodgers will likely find a way to get below $250MM this year.

It’s worth asking: if you’re not the Yankees, Astros, or Cubs, why are you so scared of the $210MM boogeyman? None of the other 27 teams need to reset – they’re already in the first-time CBT payor column. That includes the Red Sox, sitting around $204MM and letting the Blue Jays pass them up. The Angels are around $191MM. The Mets are around $187MM. The Phillies are around $196MM. The Nationals are around $194MM. That makes five teams this winter that seem to have some deference to the $210MM base tax threshold. What would be so bad about spending, say, $220MM? The tax penalty would be $2MM, exactly the price of one year of Hansel Robles.

So the Reset Club includes the Yankees, Astros, and Cubs. And then five additional teams – the Red Sox, Angels, Mets, Phillies, and Nationals – belong to the Soft Cap Club. For the other 22 teams, the luxury tax simply has no bearing, which will only be underlined if the thresholds go up significantly in the next CBA. It’s possible the eight luxury tax avoiders have grand plans for the 2021-22 free agent class – check it out – and want to be first-time payors after they go big next winter. Otherwise, it’s hard to understand why a Soft Cap Club forms every offseason.